Stupid Ewoks

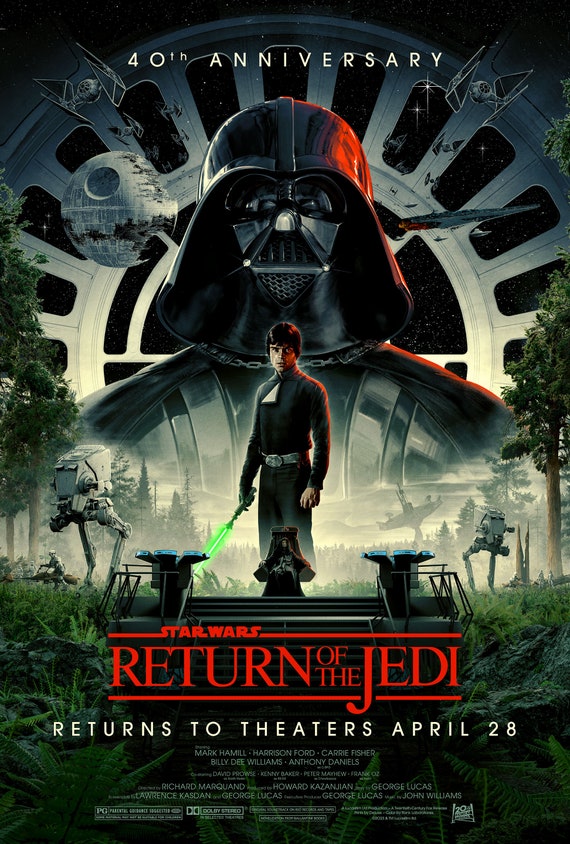

The third and final entry of the original Star Wars trilogy, the sixth Episode of the later-named Skywalker Saga, opens with a visit by Darth Vader to the Second Death Star in the making above the forest moon of Endor, with none other than Emperor Sheev Palpatine himself overseeing its construction. The action then cuts to Luke Skywalker's home planet of Tatooine, where droids Threepio and Artoo visit crime lord Jabba the Hutt's palace as part of a plan to rescue the carbonite-frozen Han Solo, Luke himself promising the pair as a bargain.

Jabba refuses and demonstrates overall that he isn't a very competent criminal since he comes to hold several high-profile members of the Rebel Alliance prisoner, encompassing the droid duo, Han, and Princess Leia, but doesn’t demand any kind of ransom for them, seeming to hold them hostage for the sake of holding them hostage (and describing Han as his "favorite decoration" in his palace). Boba Fett returns as well, with his own spinoff Disney+ series ultimately settling his fate, though Jabba’s having a son, Rotta, in the The Clone Wars pilot film still leaves to question what became of the younger Hutt.

Luke eventually comes to the rescue and gets everyone back in the Rebellion, Lando Calrissian joining their ranks and having been a part of the plot to get everyone free, with the Rebels gradually assembling to attack the Second Death Star above Endor. Before he joins the attack, though, Luke returns to Dagobah to complete his training with antediluvian Jedi Yoda, who does an about-face and says his training is complete, given his experience with fighting Darth Vader back in The Empire Strikes Back, though to become an official member of the fallen Order necessitates he defeat the Sith Lord.

Luke uses the four decades of technological progress since his dad's lightsaber was lost to build a new one and...make it green.

Obi-Wan’s Force ghost returns as well, agreeing with Yoda that Luke must confront Vader and his Sith Master the Emperor, after which comes the revelation of who the "other" the diminutive Jedi mentioned in Episode V is, and continuing the story of Luke's lineage. I know many critics and "fans" talk about the "inconsistency" of Obi-Wan not knowing of the "other hope" in Empire, although the late Jedi continues to insist that Luke is the Galaxy’s "last hope" within the film but given Kenobi’s experience with said "other hope" in his respective Disney+ series, I can semi-understand why he would feel that way.

However, Luke is hesitant to kill Vader given the iconic revelation in Episode V, believing there is still good in him, and since Obi-Wan had warned him about the young Skywalker's wish to "take the quick and easy path" to becoming a Jedi, Kenobi was pretty much going against his own advice, and had done exactly that in The Phantom Menace. Kenobi further warns that Vader is immune to redemption given that he's "more machine now than man, twisted and evil." Gee, now how exactly did that happen? Given Obi-Wan's actions before and advice to Luke, he could actually be considered one of the true villains of the Star Wars saga, too evil in fact for

Game of Thrones.Luke is initially part of the plan to down the deflector shield protecting the Second Death Star in space, but believes he jeopardizes the mission and parts ways to allow the Imperials to capture him to meet Vader and eventually the emperor in the fledgling space station, culminating in a final duel while the Rebels deal with the trap Palpatine laid for them. The final scenes between Luke and Vader are among the most emotional in the Skywalker Saga, the Rebels down on Endor overcoming the emperor's trap with the help of the local Ewok population, after which everyone across the Galaxy celebrates their sudden obtained freedom from the Empire.

Luke could've just done this instead of killing everything he came across.

While I'm mostly fine with the changes effected to rereleases of the Original Trilogy, the scenes of everyone across the Galaxy including Coruscant, Tatooine, Bespin, Naboo, et all, celebrating in my mind was one I find issue with, since the Rebels just destroyed a space station and a fraction of the imperial forces, which would be akin to the destruction of the Pentagon causing America to collapse. Throughout history, furthermore, the deaths of national leaders rarely made regimes fall as well; for instance, the Ba'athist Iraqis still fought when Saddam Hussein fell out of power.

I know a trilogy of canon novels addresses what happens post-Battle of Endor, but George Lucas wasn't completely foresightful when turning Star Wars into a franchise, given the various clashes of continuity within and without the original and prequel trilogies. Regardless, Episode VI did really move me emotionally, more so than Empire, and John Williams's score as always is good and led me to fully watch the ending credits. Overall, Return of the Jedi, regardless of its faults, has aged well and is one of the cornerstones of the series.

| The Good | The Bad |

|---|---|

|

|

| The Bottom Line | |

| Acutally the high point of the Original Trilogy. | |

|

|